Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide and it is predicted that its incidence will increase markedly, particularly in developed countries, despite the introduction of new drugs and devices. One of the factors accounting for the limited effectiveness of pharmacological therapy is poor adherence to treatment, particularly in elderly patients. The use of combinations of multiple agents in a single pill formulation could be of value in improving adherence to treatment and disease control, as well as conferring other favourable actions. In an aging population, patients with CVD will inevitably present with multiple comorbidities requiring a number of different drugs. By choosing drugs with compatible pharmacokinetic properties, the use of single pill combinations can substantially reduce the pill burden for such patients.

This article aims to briefly review the practical applications of single pill combinations in three important conditions in the cardiovascular continuum: hypertension, ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and chronic heart failure (CHF).

Hypertension

It is well established that adequate blood pressure (BP) control is essential to reduce cardiovascular risk. Hypertension is the main cardiovascular risk factor due to its high incidence, and a linear relationship exists between BP and cardiovascular events.1,2 Overall, the prevalence of hypertension is around 30–45 % in the general population, with a marked increase in the elderly.3 Despite its importance in terms of public health and socio-economics, the prevalence of hypertension has remained essentially unchanged over the last 20 years. This is due, to a large extent, to the fact that the use of BP-lowering drugs is suboptimal and a substantial proportion of patients fails to achieve BP levels recommended by current guidelines.4–7 The multinational Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study found that only a third of participants achieved BP control.8 Non-adherence to antihypertensive treatments is common, and is much higher in patients with resistant hypertension than in the general hypertensive population.9 In addition, non-adherence is difficult to monitor because most objective measures do not confirm ingestion of the medication.9 Therapeutic interventions that increase adherence are therefore of great value. Single pill combinations in hypertension have been associated with increased patient adherence.10–12

Therapeutic approaches for hypertension should consider not only BP values but also overall cardiovascular risk, which includes the presence of other risk factors and/or co-morbidities, in order to maximise costeffectiveness. Current guidelines suggest initiating antihypertensive therapy using a single drug or a pharmacological association on the basis of BP values and presence of concomitant risk factors.3 In general, monotherapy is effective in achieving normal BP values in 30–40 % of patients with mild hypertension who represent the majority of patients with arterial hypertension.3 However, combination therapies involving two classes of drugs result in a significant greater reduction of global cardiovascular, coronary and cerebrovascular events compared to monotherapy,13 and should therefore considered as initial therapy in essential hypertension.3 A meta-analysis of 40 studies concluded that combination therapy results in a greater reduction in blood pressure compared with increasing the dose of a single drug, regardless of the class of drugs used in combination.14

Potential advantages of using a single pill combination therapy as firstline treatment include: a faster reduction of BP and a greater possibility of achieving target BP, opposition to the counterregulatory pathways activated by monotherapies, improving tolerability and decreasing the adverse effects arising from up-titrating single agents. For example, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) such as valsartan can minimise the peripheral oedema caused by a calcium channel blocker such as amlodipine,15 and the combination of perindopril/amlodipine has a reduced incidence of peripheral oedema compared with amlodipine monotherapy.16 In addition, a simplified administration favours a greater therapeutic adherence compared to that expected from frequent therapeutic changes in the attempt to find the most effective drug.10,17 The availability of single pill formulations with different doses of each single drug in the same combination should reduce the problem of changing the dose of a single drug independently from the other.

The combination of two (or even three) drugs in low doses also has the advantage of reducing side-effects compared with increasing the dose of a single drug administered as monotherapy.18 The Assessment of combination Therapy of Amlodipine/Ramipril (ATAR) study examined a combination of a calcium-antagonist (amlodipine) and an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor (ramipril) in patients with grade 1 and 2 hypertension, and reported that combination therapy resulted in a significantly lower incidence of peripheral oedema (7.6 %) compared with the calcium-antagonist as monotherapy (18.7 %, p=0.011), and was associated with a significantly greater reduction in systolic-diastolic BP, measured using 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring.19 In a cohort study, the use of a single pill combination therapy, prescribed on the basis of a simplified algorithm treatment, resulted in a decrease in BP in a significantly higher percentage of patients with mild hypertension compared to the therapy prescribed on the basis of current guidelines.20 Numerous studies support the increased use of single pill combinations in hypertension,21 including Perindopril pROtection aGainst REcurrent Stroke Study (PROGRESS),22 Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT),23 Avoiding Cardiovascular events through COMbination therapy in Patients LIving with Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH),24 HYpertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET)25 and Action in Diabetes and Vascular disease: PreterAx and DiamicroN MR Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE).26

The rationale for a combination therapy relies on utilising drugs with complementary mechanisms of action that lead to a more effective reduction in BP without increasing the risk of side-effects related to increasing the dose of a single drug. The choice of drug must therefore take into account the different mechanisms that sustain the rise in BP. Although various drug combinations have proved to be effective in improving BP control, some trials based on principles of clinical pharmacology have demonstrated that certain combination therapies are more effective than others in reducing cardiovascular risk in addition to decreasing BP. Both the ACCOMPLISH24 and the ASCOT BP lowering arm (ASCOT-BPLA)27 studies have shown that a calcium antagonist/ACE inhibitor combination is more effective than the combinations of ACE inhibitor/diuretic and beta-blocker/diuretic in reducing total and cardiovascular mortality and cardiovascular events. The results of the ACCOMPLISH study appear to be of particular clinical significance as an ACE inhibitor (benazepril) was used both in the arm receiving a calcium antagonist (amlodipine) and in the arm receiving a diuretic (hydrochlorothiazide). The study enrolled more than 11,000 patients with hypertension at high cardiovascular risk and the study was discontinued early after 36 months, when the pre-specified limits were exceeded. At that point, the benazepril/amlodipine therapy group had a relative risk reduction in primary outcome events of 19.6 % compared with the group taking benazapril/hydrochlorothiazide.

The choice of pharmacological combinations is a crucial factor in the achievement of optimal BP values and in the prevention of cardiovascular events without impacting on tolerability. A 2015 editorial highlighted the fact that some combinations (e.g. calcium antagonists plus diuretics) have no additive effects, while other combinations (e.g. clonidine plus alpha-1 receptor blockers) can have a negative interaction.28 In the 2008 Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET), the combination of an ACE inhibitor with an ARB resulted in cases of severe renal failure,29 and in the Aliskiren Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Using Cardio-Renal Endpoints (ALTITUDE) study, in which a direct renin inhibitor was added to pre-existing therapy with an ACE inhibitor or an ARB, a high incidence of stroke and severe renal failure resulted in the discontinuation of the study.30

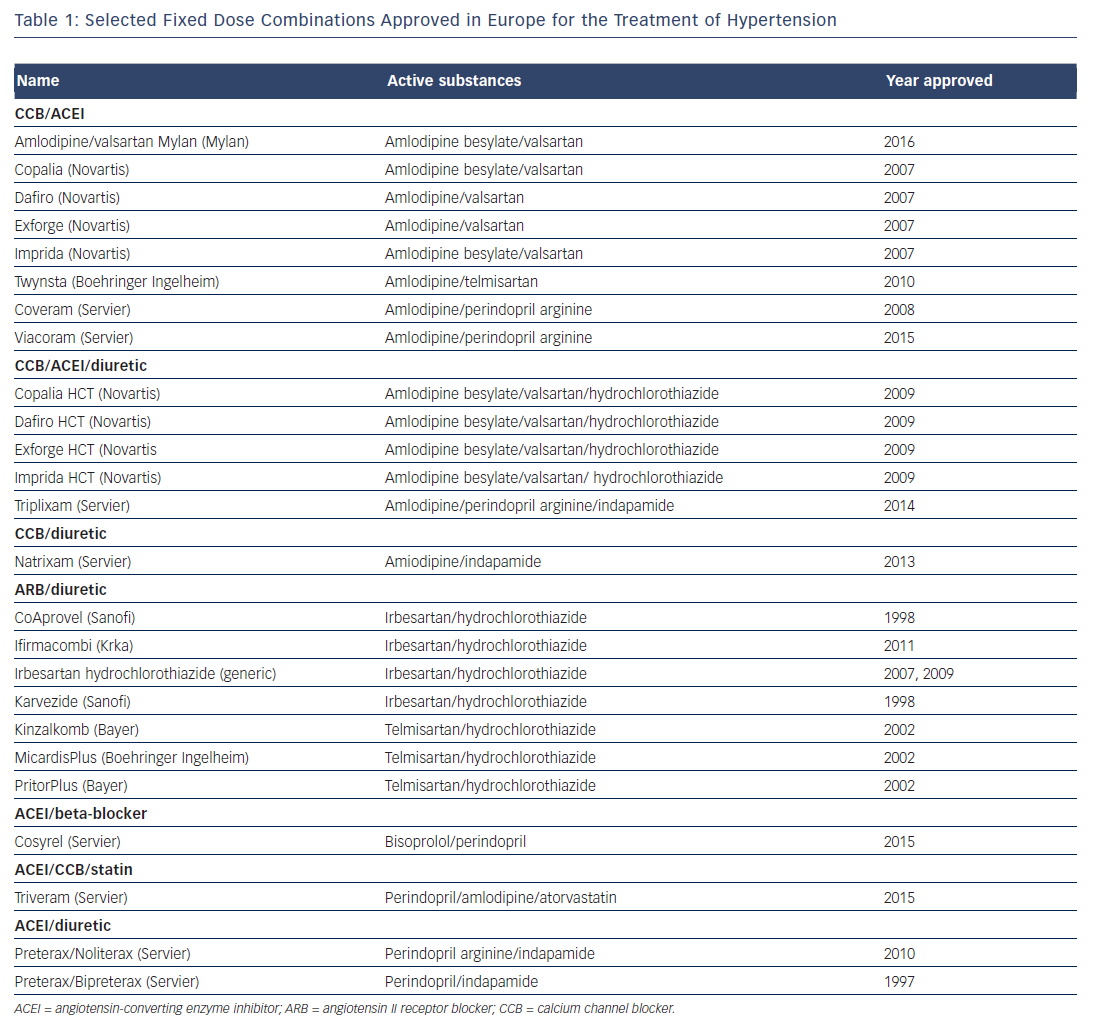

Currently available single pill combinations include ACE inhibitor/ thiazide diuretic, ARB/thiazide diuretic, beta-blocker/thiazide diuretic, ACE inhibitor/calcium channel blocker (CCB), ARB/CCB, beta-blocker/ ACE inhibitor, and beta-blocker/CCB. Triple single pill combinations such as perindopril/indapamide/amlodipine,31 are also available for patients who fail to meet blood pressure goals with the combination of two drugs (see Table 1). Recently, a small clinical trial has demonstrated the efficacy and safety of a single pill combination containing four antihypertensive drugs each at quarter-dose (irbesartan 37.5 mg, amlodipine 1.25 mg, hydrochlorothiazide 6.25 mg, and atenolol 12.5 mg) and suggested that the benefits of quarter-dose therapy could be additive across classes.32

It has also been argued that single pill combinations should be used in the early stages of hypertension; a matched cohort study found that initial combination therapy was associated with a significant risk reduction of 23 % for cardiovascular events or death compared with delayed therapy.33 A meta-analysis also supported the use of anti-hypertensive therapies even in grade 1 hypertension at low-tomoderate risk.34

In summary, increasing evidence indicates that a combination therapy of two different classes of drugs in a single pill is equally or more effective than monotherapy, even in mild-to-moderate hypertension, with an improved tolerability and safety profile. Current European guidelines recommend single pill combinations as firstline treatment for hypertension in patients with a systolic pressure higher than 20 mmHg and/or a diastolic pressure higher than 10 mmHg above the targeted goal, as well as in patients with multiple cardiovascular risk factors such as metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and heart and renal disease.3 Combination therapy is recommended in uncontrolled hypertension and should be prescribed in patients at high risk, because it offers a greater chance of achieving optimal BP control.3 In prescribing a combination therapy, the drugs should have complementary mechanisms of action. Using fixed-dose drug combinations in a single tablet should ensure better adherence to therapy, as a result of a reduction in the number of pills to be taken daily. In turn, better adherence should result in improved BP control and fewer cardiovascular events.

Ischaemic Heart Disease

Hypertension is also a major risk factor for ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and often coexists with dyslipidemia, the other main determinant of IHD.35,36 Coexistence of the two conditions results in an increase in coronary heart disease-related events that is more than additive for the anticipated event rates with each disease.37

Current treatment goals in IHD include delaying atherosclerotic progression by the use of statins and antianginal drugs to improve the imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand. However, as in hypertension, therapeutic goals are rarely attained.38 The National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel 3 guideline recommends aggressive management of patients with concomitant hypertension and dyslipidaemia.39 The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the management of stable coronary artery disease involve an algorithm containing two components: event prevention, typically comprising statins, aspirin, ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and treatment of symptoms, usually involving beta-blockers.40 Therefore single pill combinations are a logical means of simplifying treatment regimes. In addition, a substantial proportion of patients remain symptomatic despite optimal doses of first-line treatment. Combined therapeutic regimens offer a potential way to address this unmet need.

As a result of the pill burden, adherence to cardiovascular drugs is low among patients with IHD, even lower than in hypertension. Adherence to concomitant antihypertensive and lipid lowering therapy is particularly poor, with only one in three patients adherent with both medications at 6 months.41 These findings emphasise the likely relevance of using single pill combinations drugs in IHD.

A preventive therapeutic strategy consisting of a single pill combination of low doses of statin, two antihypertensive drugs, aspirin and folate was first proposed by Wald and Law who suggested that such a polypill might reduce CVD by 80 % and might be prescribed to everyone over the age of 55 without the need for screening.42

The polypill approach has been studied in several clinical trials of patients with low to moderate CVD risk. A meta-analysis by Elley et al indicated that, compared with placebo, polypills reduced blood pressure and lipids, whereas tolerability was lower.43 The Use of a Multidrug Pill in Reducing Cardiovascular Events (UMPIRE)44 and IMProving Adherence using Combination Therapy (IMPACT)45 trials found that the use of such a strategy in patients with or at high risk of CVD resulted in significantly improved adherence at 15 months compared with usual care and a modest, yet significant, improvement in systolic BP and LDL-cholesterol, although no significant differences in cardiovascular events were detected. Similarly, a 2014 Cochrane review of trials from higher risk populations concluded that the effects of single pill combination therapy on all-cause mortality or CVD events are uncertain since few trials reported on the above outcomes, although single pill combinations were associated with improved adherence, reductions in BP and improved lipid parameters.46

Improving quality of life and symptom control are primary goals of angina treatment, whereas many studies using a single pill combination therapy have focused only on secondary prevention. Indeed, the recent Angina Prevalence and Provider Evaluation of Angina Relief (APPEAR) study found that many patients with angina are symptomatic but this is underacknowledged and undertreated by physicians.47 In particular, the effect on quality of life is often neglected in angina treatment. Living with angina is associated with functional limitations in terms of physical activity, social and emotional health status, and angina is associated with both an adverse health-related quality of life and higher levels of depression.48 The beneficial effect of beta-blockers, the most often used antianginal drugs, on quality of life is only small, but can be considerably improved by the addition of ivabradine. Ivabradine and beta-blockers have complementary and synergistic mechanisms of action, improving the balance between oxygen supply and demand to the ischemic myocardium.49 The combination of ivabradine and beta-blockers has been shown to reduce the number of angina attacks, nitrate consumption and improve quality of life, in addition to slowing heart rate, in patients with stable angina pectoris.50,51 In particular, the combination of ivabradine and metoprolol has proven effective and safe in patients with angina.52–54 A study evaluating combination therapy with non-maximum dose of beta-blockers and ivabradine compared with up-titration of beta-blockers in patients with stable angina found that the up-titration group experienced twice as many adverse reactions as the ivabradine group.55

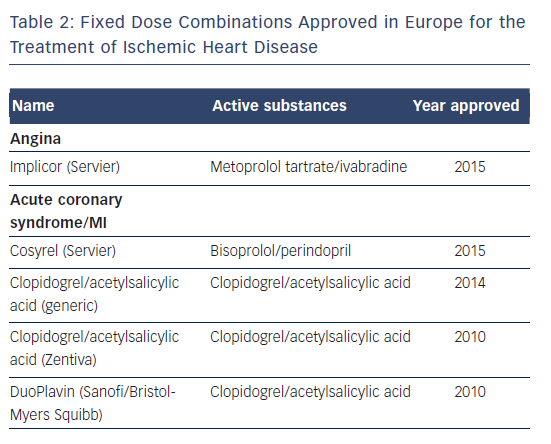

A single pill combination of ivabradine plus metoprolol at different fixed doses (Implicor, Servier) has been approved recently in Europe as substitution therapy (see Table 2),56 and might prove beneficial in terms of adherence to treatment, which could further improve the antianginal effects of this combination therapy. Recent data from a large prospective, multicentre, observational cohort study of 610 patients with chronic stable angina, showed that an ivabradine/metoprolol single pill combination reduced heart rate, angina symptoms and nitrate consumption, as well as improving exercise capacity. Tolerability of the combination was rated as very good in 74 % of cases and good in 25 %.57 A systematic review concluded that the use of single pill combinations increases adherence in the secondary prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events in individuals with established CVD.58 At present, a potential disadvantage for single pill combination therapy in angina patients is the relative lack of dosing flexibility for its individual components. Availability of multiple forms of fixed dose combinations incorporating different dosages will ensure dosing flexibility for its individual components. However, the advantages of single pill combinations, such as beta-blocker/ACE inhibitor or betablocker/ ivabradine, outweigh the limitations and offer substantial benefits in terms of improved efficacy and reduced pill burden.

Heart Failure

Chronic heart failure is at the end of the continuum of CVD and despite recent clinical advances, the prognosis for this condition remains poor,59,60 while its prevalence is expected to increase markedly. In patients with CHF, an add-on therapy approach is typically used, beginning with diuretics, then adding ACE inhibitors (or ARBs) and beta-blockers, followed by mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. The complexity of drug regimens for CHF has led to suboptimal therapeutic adherence,61,62 which is associated with worse clinical outcomes.63

In CHF patients the altered haemodynamic homeostasis is associated with an increased heart rate (HR), associated with a negative prognosis, whereas the beneficial effect of beta-blockers has been linked to their HR-lowering effect.64–66 However, beta-blockers are often underused in clinical practice, are seldom prescribed at the doses proven to reduce events,67–69 and their up-titration in response to persistently elevated HR can be associated with an increased risk of adverse reactions.70

A number of studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of ivabradine in combination with beta-blockers, particularly carvedilol.71–75 Ivabradine selectively and specifically inhibits the If current in the sinoatrial node, thus reducing HR without affecting the autonomic nervous system.76,77 The effectiveness of ivabradine in CHF has been evaluated in the Systolic Heart Failure Treatment with the If inhibitor Ivabradine (SHIFT) study, in which 6,558 patients with CHF on stable background therapy, including beta-blockers, and a HR >70 BPM with sinus rhythm, were randomised to ivabradine (up to 7.5 mg twice daily) or placebo.71 At the median follow-up of 22.9 months, the results indicated an improved clinical outcomes: 18 % reduction in the primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular death or hospitalisation for worsening HF, a 26 % reduction in hospitalisation for worsening HF and a 26 % reduction in pump failure death in the ivabradine group. Since the majority of patients in the SHIFT study were taking beta-blockers, it was hypothesised that the combination of beta-blockers plus ivabradine per se rather than the dose of beta-blocker was relevant to these findings. A subanalysis of the SHIFT study appeared to confirm this hypothesis, by showing that combination of drugs rather than the dose of beta-blockers were important in improving the primary endpoints of cardiovascular death and hospitalisation.78

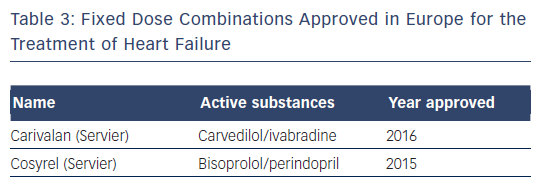

A further study concluded that the combination of beta-blockers plus ivabradine resulted in improved outcomes regardless of the individual beta-blocker prescribed.73 Studies to date indicate that the combination of ivabradine and beta-blockers is safe and well tolerated, and as a result the combination is recommended in the 2016 ESC guidelines.79 At present, dozens of countries market the combination of ivabradine and carvedilol (Carivalan, Servier; see Table 3). A subanalysis of the SHIFT study found increased cardiovascular improvements with all co-prescription of ivabradine and beta-blockers, particularly carvedilol.73

Conclusion

There is growing evidence to support the use of single pill combination drugs in the continuum of CVD from arterial hypertension to ischaemic heart disease and chronic heart failure.

There is a need to improve efficacy, acceptability, tolerability and adherence in cardiovascular medicine. Fixed-dose combination formulations offer many of these potential advantages. Furthermore, single pill combinations offer advantages in terms of cost effectiveness, making them an attractive option in low-income countries. However, single pill combinations may also have disadvantages, such as less flexibility in altering doses and differences in the duration of action of the combined drugs.

Single pill combinations are recommended by regulatory bodies as first-line treatment in arterial hypertension.3 Current ESC recommendations state that the benefits of combination use may outweigh the risks in a selected group of people with HF for whom other treatments are unsuitable.79 At present, however, there is a lack of single pills for many combinations of drugs.

In summary, there is a need for single pill combinations in cardiovascular medicine. However there is a need for further data to establish the long-term safety and efficacy of such combinations. The results of ongoing clinical trials in several countries in primary and secondary CVD settings will evaluate the clinical implications of the routine use of single pill combinations.