ESC Guidelines for Patient Self-management in Chronic Heart Failure

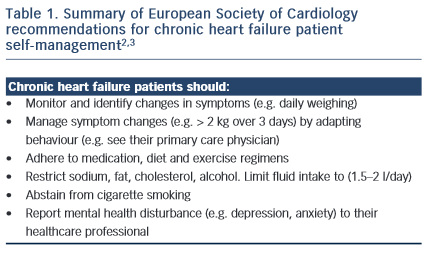

The gold-standard of patient self-management in chronic heart failure (CHF) can be defined as “daily activities that maintain clinical stability”.1 This requires that patients monitor their symptoms, adhere to their medication, diet and exercise regimens and manage symptoms by recognising changes and responding by either adapting behaviours or by seeking appropriate assistance.2 Patient self-management is linked to reduced mortality risk and fewer hospital admissions; however, there is less certainty with regard to the benefits of some aspects of self-care, such as lifestyle choices and fluid restriction.2 According to the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure,3 self-management is integral to achieving best patient outcomes: to reduce mortality and improve quality of life.

Self-management in CHF usually involves behavioural adaptation. Patients may need to learn new behaviours, such as learning how to monitor and manage symptoms and complex medical regimens. Patients may also need to abstain (e.g. cease smoking), adapt (e.g. restrict their sodium, cholesterol and fluid intake) and maintain (e.g. exercise regularly) other behaviours. While targets have been recommended for best CHF management practice (such as to restrict fluid to 1.5 litres per day and to monitor weight changes > 2 kgs over three days), these need to be individualised according to the patient symptom and disease status profile and reset regularly. From the patient perspective, this increases the complexity of self-management and intensifies the cognitive, behavioural and motivational demands of self-care. However, for most patients the empowerment rendered by self-care results in a sense of control and achievement, rather than a feeling of passivity and helplessness. This applies to the partners of patients, as well as to the patients themselves. Within the general framework of the management strategy, the patient must experience some sense of control. For example, the patient needs to control the diuretics – the diuretics should not control the patient. Thus flexibility of dosage timing needs to fit in with the sociological constraints of the patient’s day-to-day life.

It is also important to stress that self-care can only work satisfactorily when there is partnership with – and trust in – the healthcare professional team. For example, even in the absence of cognitive impairment, a patient cannot safely alter their own diuretic doses (as a response to their weight and fluid status) unless the parameters are regularly reviewed and reset at a clinic visit. Changes in adipose tissue and muscle mass can render previous “target weights” incorrect, resulting in either heart failure decompensation on the one hand or dehydration on the other, especially for relatively unstable patients. Therefore re-setting of weight targets is very important – but takes considerable clinical skill. Evaluation of volume status includes clinical assessment of symptoms suggestive of either hyper- or hypo-volaemia; measurement of blood pressure, both recumbent and standing; evaluation of jugular venous pressure with patient propped up at 45 degrees, as well as lying flat (ensuring that the veins fill appropriately); rise or fall of serum creatinine and estimation of B-natriuretic peptide. The target weight for the patient self-management can then be reset.

Self-management Interventions in CHF: Do They Work?

Patient self-management is proposed to be a cornerstone of CHF outcomes,3 although evidence to support this is limited.4 Nonetheless, poor patient adherence is linked to hospital readmissions.5,6 Patient disability, disease burden and decompensation undermine adherence to recommended self-management behaviours.7,8 Non-adherence to recommended treatment plans is common in CHF,6,9 with reports that up to 60 % of patients do not adhere to their medication regimens as prescribed and up to 80 % do not adhere to lifestyle recommendations.5,10 Van der Waal et al6 also found that patients tend to tolerate exacerbations in their CHF symptoms and delay seeking assistance.

Health literacy has also been linked to a patient’s ability to self- manage.9 Low health literacy has been shown to be an independent predictor of mortality11 and hospitalisations.12,13 It is unknown as to whether poor health literacy is a primary cause of poor health outcomes or whether it is an underlying problem of other issues, such as low socioeconomic status, inadequate access to health services or a low trust in healthcare providers. Nevertheless, low health literacy needs to be addressed in an effort to improve knowledge and self- management skills.

A variety of strategies has been proposed to support patient self- management, such as early and targeted screening of patients to identify and resolve capacity deficits (e.g. limited literacy, cognitive and physical impairment) and psychosocial obstacles (e.g. depression and anxiety) that may undermine self-care. For example, whole system informing self-management engagement (WISE) training involves an assessment of patient needs, motivation and capacity, shared decision making and agreement on a management plan to support patient self- care; WISE training has produced improvements in patient outcomes in several chronic disease settings,14 but is untested in CHF.

Both depression and anxiety are associated with poor adherence to medical regimens,15 this in turn having a marked effect on patient self-management. The management of depression in cardiac patients therefore is extremely important if patients are to become engaged in self-management.16 The importance of a relevant professional relationship, with continuity over time, cannot be over-emphasised for the maintenance of patient engagement, collaboration and appropriate self-management.

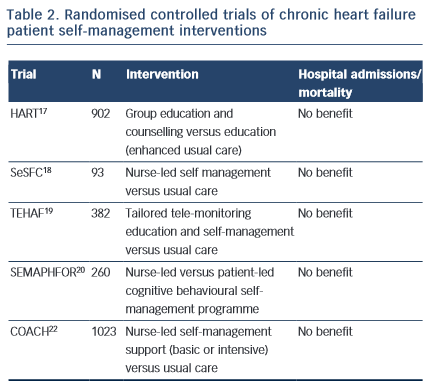

Specialist programmes were introduced to address the individual and complex care requirements in CHF and to encourage patient self- management. The HART trial17 targeted patient capacity and willingness to self-care through group education and counselling to optimise “self-monitoring, environmental restructuring, elicitation of support from family and friends, cognitive restructuring and the relaxation response” (p. 1333). A total of 902 CHF patients were randomised to an education and counselling programme or to education alone (enhanced standard care). Outcomes were assessed after 12 months; the study did not show a benefit of self-management counselling on mortality or hospital readmissions compared to education alone. Shao et al18 found that CHF patients who were randomised to a 12-week nurse-led self-management programme, which emphasised patient self-efficacy to control sodium and fluid intake (SeSFC), showed significantly better symptom control and management than usual care patients, but that both groups had similar health service utilisation. In the TEHAF study, Boyne et al19 randomised CHF patients to a tailored tele-monitoring education and self-care programme or to usual care. No significant differences in hospital admissions or length of stay in hospital were observed between groups over a 12-month period. Smeulders et al20 found that the self-care benefits of a 6-week nurse-led CHF self-management programme were no longer evident six months post-treatment compared with patients who had been randomised to usual care. The SEMAPHFOR trial21 found no difference in hospital admissions/readmissions, self-care, or quality of life between CHF patients randomised to either a nurse-led or patient-led cognitive behavioural self-management programme.

Self-management interventions are often embedded within theoretical frameworks, such as Bandura’s social cognitive theory, that emphasise patient self-efficacy (i.e. perceived capacity to meet behavioural challenges) as fundamental to behaviour change. Research evidence to support a pivotal role for self-efficacy in the clinical outcomes of CHF self-management is, however, limited. The COACH trial22 randomised 10 CHF patients23 to one of two specialist CHF nurse support programmes (basic or intensive) or to usual care. CHF nurses were trained to optimise patient self-efficacy and patients were engaged in behavioural modification strategies. The study failed to identify a benefit of treatment on mortality or hospital readmission compared with usual care.

Taken together, these findings suggest that interventions designed to support patient self-management may improve symptom monitoring and compliance,6 but fall short of reducing mortality risk or hospital admissions. While it is possible that such symptoms may not be adequate markers of CHF exacerbation,23 poor patient engagement in self-management interventions probably explains at least some of the limited efficacy of such programmes. To our knowledge, the extent to which patient engagement may have been undermined by known psychosocial confounders, such as depression, has not been reported and would be a useful addition to future research.

Nevertheless, there will always be some inherent limitations. Symptom and weight changes are generally the results of fluid retention and volume overload. However, volume changes tend to be consequent to pressures changes and therefore could be a relatively late indicator for mandating management changes, such as changes in diuretic dosage. A new approach has been to use implanted devices for measuring pressure change. Examples include devices that can directly measure left atrial pressure or pulmonary artery pressure. Monitoring of pulmonary pressure, for example, provides important information at least a couple of days before changes in patient weight are apparent. Thus, a change in diuretic dosage can be instituted earlier and this has been demonstrated to be effective in significantly reducing heart failure hospital admissions.23 This kind of direct monitoring still involves some degree of patient collaboration and self-monitoring, with the patient being given instructions based on the measured pressures. However, in the future, devices are only likely to be used in selected individual patients.

Recommendations to Promote Patient Self-management: a Social Network Approach

There is no evidence to suggest a benefit of self-management interventions on clinical endpoints in CHF at the present time and the composition of such programmes is empirically unsubstantiated.6,24 Specialist CHF outpatient programmes have yet to demonstrate an improvement in patient adherence compared to rates achieved in primary care.25 A small number of studies have observed benefits of group self-management interventions in other chronic disease settings, such as diabetes;26,27 however, the active component/s driving success of these programmes is unknown.14,28 We do know that patient education is not sufficient to engender self-care,1,29 but that it may be useful when embedded in e-health programmes.30

Lainscak et al2 suggest that patient self-management may be improved through “comprehensive CHF education and counselling that is not only focused on knowledge, but also on skills and behaviour” (p.21). The extent to which health professionals are equipped to enact such strategies, such as to provide a “non-threatening climate and an inspiring learning atmosphere” (p.3), is varied31 and requires specialist education and training.32 Kennedy et al14 suggest that, even after having participated in training, healthcare staff may be resistant to engaging in interventions designed to optimise patient self-management. They recommend a systems approach to self- management that integrates support for patients, practitioners and service providers; however, evidence of efficacy and the training and resource requirements to implement such programmes are needed.

Wingham et al33 suggest that self-management “is dependent on a range of factors including social and personal influences in conjunction with healthcare systems and health professionals” (p.150). Indeed, research suggests that the link between patient confidence and self- care1,34 may depend on the quality of the patient–health professional relationship.35 However, problematic patient-physician interactions continue to be among the most commonly reported barriers to patient self-management,36 e-health strategies will likely form a pivotal role in addressing these shortfalls. Trials in progress, such as PROMETHUS37, BEAT-HF38 and CHF-CePPORT39 will examine whether e-health platforms can overcome patient barriers, such as cognitive impairment, to improve self-management in CHF. Related work points to the potential for e-health to be integrated into patient social networks to optimise self-management.

Health-promoting, social support may improve patient self- management behaviours.7,40,41 Vassilev et al42 recommend a shift in the way we conceptualise patient self-management “from individualised, behaviour-based interventions to community and network-centred approaches” (p. 73); i.e. from patient self-efficacy towards collective efficacy.43 Peer-support programmes have shown improvements in patient self-management in some chronic diseases settings, such as diabetes. For example, the ROMEO trial27 showed a significant benefit of group education sessions for diabetes patients, scheduled quarterly over a period of two years, on knowledge, health behaviours and quality of life outcomes compared with usual care. Reeves et al44 found that self-management was associated with social connectedness and that the support offered by social networks was responsive to the changing needs of heart disease and diabetes patients. Although Heisler et al45 found no benefit of a CHF peer-support programme compared to usual care on hospital readmissions or mortality, most of the participants did not engage with the programme. Poor engagement in self-management interventions, whether at the level of the patient or practitioner, is common; e-health strategies may offer a means by which to more seamlessly integrate programmes into existing systems of care, patient lifestyles, and their social networks.46

E-health self-management interventions may improve symptom control and monitoring in chronic disease;28,47,48 however, the long-term benefits (such as reduction in hospital admissions and mortality risk) are not yet clear. Nonetheless, there is potential to harness social networks via social media platforms to enhance self-management49 and some evidence to support this approach in diabetes patients.50 The Internet Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (ICDSMP) is a web-based programme with links to self-management tools and resources and social discussion forums to explore “problem solving, action planning, difficult emotions, and celebrations”.51 From baseline to 6 months post-enrolment in the ICDSMP, the authors reported a significant reduction in hospital emergency attendances, with a non-significant trend at 12 months (P=0.049); a randomised trial is needed to confirm these benefits. Other approaches, such as the PLANS initiative, use e-health platforms to tailor access to community resources as a means by which to support self-management as it is contextualised in everyday life.52 Future investment in randomised controlled trials will enable us to evaluate the clinical, quality of life, and economic benefits of these interventions.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Self-management is considered a cornerstone of CHF outcomes; however, poor patient adherence is common. Patients and their partners may be empowered to self-care through a supportive relationship with their healthcare professional, but can be limited by the complex demands of maintaining their regimen. Strategies designed to optimise patient self-management have shown some success in improving symptom monitoring, but these have not translated to reduced hospital admissions or mortality risk. There is high-level evidence to support patient medication adherence, exercise training and smoking cessation to reduce hospital admissions and mortality risk.3 Conversely, evidence to support a morbidity and survival benefit of other patient self-care behaviours (such as symptom monitoring, restricted fluid, sodium and diet, and optimised mental health) is less conclusive. The Patient Care Committee of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology2 provides a good summary of the evidence – and evidence gaps – supporting patient self-management. Future research that systematically evaluates programme components to identify drivers of positive outcomes is needed to develop this evidence base.

New work in this field that adopts e-health technologies, such as the PROMETHEUS,37 BEAT-HF38 and CHF-CePPORT39 trials, will undoubtedly inform future practice. Recent developments point to a role for social networks in self-management support,42 although efficacy is not yet well-established. Vassilev et al43 suggest that social networks may effect change in self-management by improving awareness and access to network resources, adjusting social roles, relationships and communication in response to needs and through collective efficacy to achieve behavioural goals. Future research that harnesses a social network perspective to enlist and mobilise collective resources through e-health interventions may improve self-management in chronic disease settings.