The prevalence of major depression in chronic heart failure (HF) is about 20–40 %, which is 4–5 % higher than in the normal population.1–3 Depression in heart failure has become a major issue as the burden of heart failure has continued to increase, and many studies have suggested poorer outcomes in HF patients reporting depression.4–8 The cost of managing HF has continued to escalate, and high rates of depression contribute to this.9–13 The use of different methods for assessment (validated questionnaires and clinical interviews) and the effects of age, gender and race have contributed to variations in the prevalence figures reported. Antidepressant drug therapy has not yielded the desired outcomes. Even the use of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) has not shown a consistent improvement in outcomes, as demonstrated by two recent large trials.14,15

Prevalence

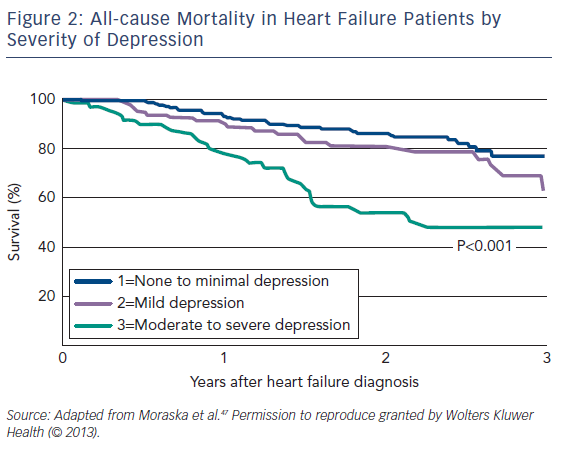

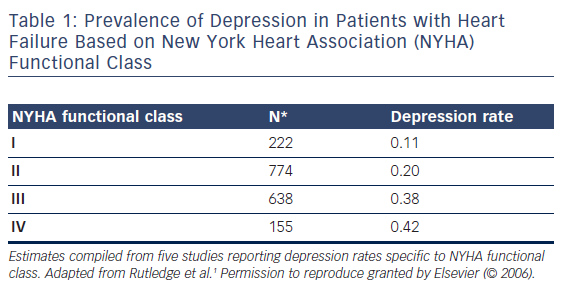

The aggregated point prevalence of depression in HF patients is about 21 %;1 however, the figures reported in studies range from 9 to 60 %.1 The aggregated prevalence for women is higher than for men, with 32.7 % (range 11–67 %) of women being depressed compared with 26.1 % (7–63 %) of men.1 The prevalence of depression increases with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, with the biggest difference seen between NYHA classes II and III (see Table 1).

The heterogeneity in the reported prevalence of depression is related to various factors, such as: the method of assessing depression (questionnaire versus structured interview); conservative versus liberal cut-offs for depression diagnosis; the severity of HF, mean patient age, ethnicity and gender; and inpatients versus outpatients.

The plethora of depression symptom inventories, including the Beck depression inventory,16 Zung self-rating depression scale,17 geriatric depression scale,18 Center for Epidemiological Studies – depression scale,19 hospital anxiety and depression scale,20 inventory to diagnose depression,21 Hamilton rating scale for depression,22 Hopkins symptom checklist,23 medical outcomes study – depression24 and multiple affect adjective checklist,25 has also contributed to the heterogeneity (see Figure 1).

Pathophysiological Implications of Depression in Cardiovascular Disease

The adverse effects of depression on cardiovascular disease (CVD) are believed to be mediated by a shared pathophysiological mechanism. Natriuretic peptides in HF are altered in areas of the brain regulating blood pressure and fluid control in experimental animals.26 Drugs used in the treatment of HF may reverse these changes.27 Central natriuretic peptides have an antagonistic effect on blood pressure and fluid neurotransmitters in HF, and are associated with mental and emotional changes in HF.28,29

Depression may contribute to dysregulation of the autonomic system, with reduction in the parasympathetic and increase in the sympathetic tone and its attendant increase in heart rate, reduction in heart rate variability and lower threshold for myocardial ischaemia and adverse cardiac events in patients with CVD.30,31 The heightened sympathetic tone is associated with increased levels of cortisol,30 serotonin, renin, aldosterone, angiotensin and free radicals.3 High levels of circulating catecholamines may also induce a pro-coagulant phase by increasing platelet activation32,33 and inhibiting the synthesis of protective eicosanoids in response to the increased haemodynamic stress on the vascular wall.34 Reduced inhibition of macrophage activation via the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway contributes to the elevation of pro-inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein and cytokines, such as interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), in depression. TNF-alpha administration in healthy subjects has been shown to reduce serotonin levels and produce depressed mood, sleep disorders and malaise.35,36

A number of other mechanisms for poorer outcomes in depressed HF patients have been proposed in the literature. It has been suggested that inflammation may be responsible for worse outcomes in depressed HF patients.37 High levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 and TNF-alpha, are independent predictors of HF-related deaths and exacerbations.38–40 Despite this suggestion, however, the evidence linking outcomes in HF patients with depression to individual biomarkers is still debatable. Recently the effect of reduced blood flow to the hippocampus, which has an important role in emotion and memory, has been alluded to as a possible mechanism for depression and cognitive decline in patients with HF.41 Experimentally there is strong evidence for the modulating role of the immune system on the relationship between depression and CVD via the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the autonomic nervous system.42

Despite these interrelationships between depression and CVD, no causal relationship has yet been demonstrated. Most of the studies in this area were case-controlled or cross-sectional, but they did not control for behavioural mediators such as poor treatment adherence.

The Management of Depression in Heart Failure

There is still no consensus on the best way to treat HF patients with depression. Studies have shown improvement in depressive symptoms with the use of SSRIs;14,15,43,44 however the large Setraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in Chronic Heart Failure (SADHART)14 and Morbidity, Mortality and Mood in Depressed Heart Failure Patients (MOOD-HF)15 trials failed to show any significant benefit over placebo. No clear benefits were shown between usual care (optimal HF treatment without antidepressants) and the use of SSRIs in SADHART or MOOD-HF.

Psychotherapy has been shown to reduce the depressive symptoms in CVD but has no effect on the major outcomes of the disease.45 A small study comparing Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy with a web-based discussion forum did not demonstrate a significant difference in the management of depression in HF. There was, however, a significant improvement in depressive symptoms of the Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy group when compared with baseline.46

Outcomes in Depressed Heart Failure Patents

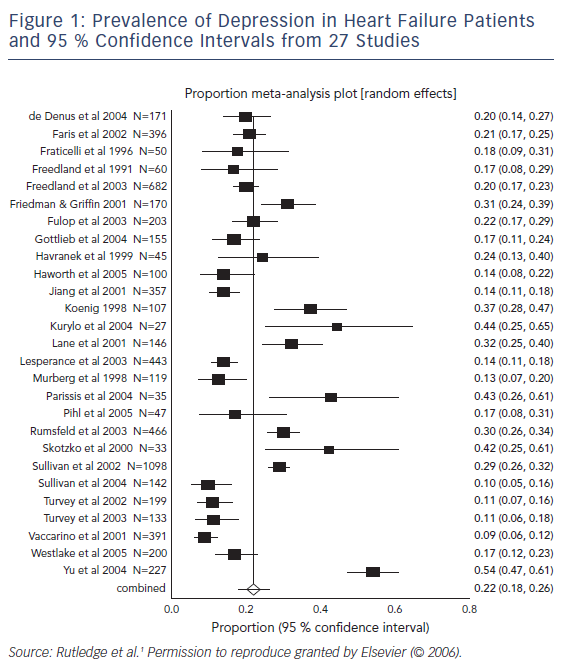

Studies have suggested a worse outcome in HF patients with depression across a broad range of events including mortality, healthcare use and associated clinical conditions, especially in more severely depressed patients (see Figure 2).1,47 Depression was found to be an independent risk factor for mortality in HF, and this persists independent of NYHA class.7

A recent large Danish study found depression to be related to allcause mortality in patients with an ejection fraction ≤35 % but not in other types of HF.48 There was no interaction between mortality and age, sex, HF cause, NYHA class or comorbidities. Depression in HF has also been shown to be the strongest predictor of short-term declines in health status, significant worsening of HF symptoms, physical and social functions, and quality of life.8

A meta-analysis of nine studies shows that the relationship between depression and mortality is dependent on the severity of depression: severe and not mild depression are associated with increased mortality.49 The increased mortality related to depression in HF persists over a long period of time.50 Depression is associated with death and readmission for HF, especially in patients with milder HF, a shorter duration of symptoms and lower blood pressures.51

There are a number of factors that could lead to the overestimation of the impact of depression on mortality. These include differences in the method of diagnosing depression, self-reported depression symptoms or antidepressant use, and inability to account for confounders such as smoking and alcohol use.1,7,47

Conclusion

Depression is a common finding in patients with HF and constitutes an additional burden on the management of these patients. Wide variations in reported prevalence rates are due to varied cohort characteristics and the multiplicity of instruments and methodologies used. The presence of depression, however, leads to poor outcomes, morbidity and mortality. Treatment with newer SSRIs, although effective, does not improve outcomes and is not superior to cognitive behavioural therapy and psychotherapy. There are still many knowledge gaps to fill and issues to be addressed.